Letters from a long-suffering poet, 1966

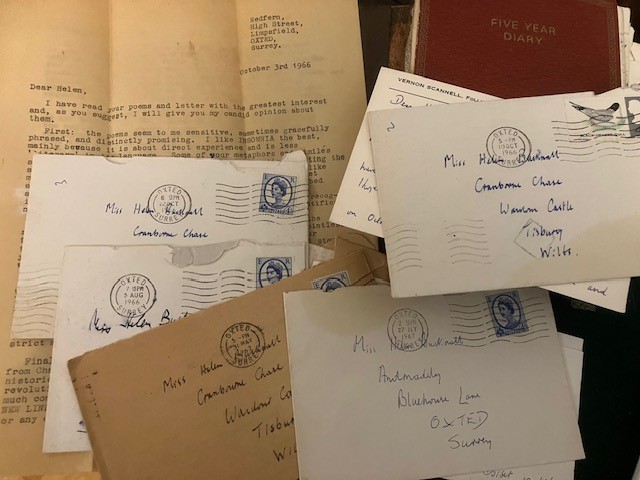

Yesterday, I found eight faded letters

lying loose in the covers of a battered red diary.

Letters, some fifty years old, from a poet,

responding to the teenage poems I had sent.

The envelopes are yellowed, the paper thin,

stamps in shillings and pence;

the words, typed accurately on a portable Olivetti

or spider-thin script on postcards.

What a patient man he was, Vernon Scannell,

to while away his poetic hours on my juvenile verse,

advise me on a career allowing me time to write.

“No-one ever makes money from poetry,” he wrote.

He lived in a terraced cottage in my village, Limpsfield,

next to my favourite bookshop in the narrow High Street.

I discovered that he was court-martialled as a deserter.

He became a boxer.

To me though he was kind and tolerant,

answering my questions, commenting on my poems:

observation that could hit as hard as his boxing glove.

I’m glad I thanked him before he died.

He helped me shape a life around books,

suggested a job in publishing

and encouraging me to write and read, and sweat

to get to the emotional and intellectual truth of the matter.

I shared with him the poems in the school magazine,

and met him at the Festival Hall;

he was reciting poetry with Dannie Abse,

accompanied by a 60s jazz band.

‘You’re only sixteen,’ he wrote. ‘You’re not ready for publication.’

He’d died by the time my first poems were published,

the prizes awarded. But the dusty letters remain,

his voice in my head repeating and repeating ‘be ruthless with the adjectives’.